Section 4 - Harm II

We started discussing the harms (negative impacts) on people who use systems powered by large language models. We call these behavioral harms because these are harms due to the behavior of a language model rather than its construction (which would encompass data privacy and environmental impact).

So far, we have described two types of behavioral harms:

- Performance disparities: a system is more accurate for some demographic

groups (e.g., young people, White people) than others (e.g., old people, Black people).

- Example: language identification systems perform worse on African American English (AAE) than Standard English (Blodgett et al. 2017):

Example: Amazon’s automatic resume screening was biased against women,

downweighting

- Social bias and stereotypes: a system’s predictions (generated text)

contains associations between a target concept (e.g., science) and a demographic group (e.g., men, women),

but these associations are stronger for some groups than others.

- Example: autocomplete systems make gendered assumptions (Robertson et al. 2021) (demo)

Recall that these harms are not unique to

- large language models,

- or even language technologies,

- or even AI technologies.

But it is important to study the harms of language models because:

- they have new, powerful capabilities,

- which leads to increased adoption,

- which leads to increased harms.

Benefits versus harms. With any technology, it’s important to consider the tradeoff between benefits and harms. This is very tricky business because:

- It is hard to quantify the benefits and harms.

- Even if you could quantify them, the benefits and harms are spread out unevenly across the population (with marginalized populations often receiving more harms), so how one makes these tradeoffs is a tricky ethical issue.

- Even if you could meaningfully tradeoff, what legitimacy does the the decision maker have? Can Facebook or Google just unilaterally decide?

Upstream versus downstream.

- We are considering harms of a system in the context of a downstream task (e.g., question answering).

- These systems are adapted from large language models.

- We would like to understand the contribution of the upstream language model on harms.

- This is increasingly meaningful as the adaptation becomes thinner and the large language model does more of the heavy lifting.

Overview

Section titled OverviewIn this lecture, we will discuss two more behavioral harms:

- Toxicity: large language models generating offensive, harmful content

- Disinformation: large language models generating misleading content

Before we dive in, we should point out a disconnect:

- Language models are about text. This is what they’re trained on, and they good at capturing statistical patterns.

- These harms are about people. It is about a person receiving a piece of text and feeling upset or hurt by it. This means that we need to think of the harms as not a property of the text, but in terms of the broader social context.

Content moderation

Section titled Content moderationBefore we get to large language models, it is helpful to ground out toxicity and disinformation in the very critical problem of content moderation.

- Sites such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube are constantly waging a war against people who post or upload harmful content (hate speech, harassment, pornography, violence, fraud, disinformation, copyright infringement). For example, Facebook’s Community Standards provides a broad list of things that are prohibited from the platform.

- Companies are under increasing pressure from government to keep online spaces safe for people.

- Given the scale of these companies, it is infeasible (and also inhumane) to perform content moderation manually, and gradually, companies have turned to AI to automate the process.

- The result of moderation could be hard (blocking, deletion) or soft (flagging, hiding).

- Note that decision of what is allowed is fundamentally political - What is a terrorist organization? What speech is allowed?

Context-dependence. What constitutes harmful content is very context-dependent. Chandrasekhran et al. 2018 performed a detailed study on Reddit:

- 2.8M removed comments from 100 subredits over 10 months and

- asked how norms vary across different subreddits.

While there are norms common to almost all subreddits, many norms are specific to subreddits, for example:

- No personal reactions/opinions: “and this is why i love science, always on the pursuit of knowledge”

- No links to illegal livestreams: “free live streaming chicago bulls los angeles lakers basketball”

Dual use. There are two ways in which language models can be used in the context of toxicity and disinformation:

- They can be used to generate toxic content. Malicious actors can use it to amplify their message.

- They can be used to detect disinformation and thus aid in content moderation.

Toxicity

Section titled ToxicityWe want to understand the harms of large language models related to toxicity. There are two possible recipients of the harm:

- The user of the LM-based system.

- A chatbot could reply with a toxic response.

- An autocomplete system could make a toxic suggestion.

- The recipient of the user-generated content.

- The user, with or without malicious intent, might post the toxic content on social media.

Working definition. What is toxicity? As mentioned above, harms are about what happens to people, so it is important to remember that the definition is very context-dependent. To make some progress, we can use the following working definition: Borkan et al, 2017 defines toxicity as anything that is “rude, disrespectful, or unreasonable that would make someone want to leave a conversation.” Examples:

- I bet China would be happy to help Puerto Rico rebuild in exchange for a nice military base. [toxicity: 0]

- The ignorance and bigotry comes from your post! [toxicity: 80%]

Word lists. How far can one get by simply defining toxicity in terms of presence of certain “bad words”?

Aside: The Clossal, Cleaned Common Crawl (C4) dataset was filtered using this word list and used to train the T5 language model. We will talk about the complexities of data later in the course.

Using a word list is inadequate because:

- Genuinely harmful text contains no bad words.

- Example: A trans woman is not a woman.

- Non-harmful text do contain bad words.

- Example: words used in the context of healthcare or sex education

- Example: profanity in fiction

- Example: slurs used by groups to reclaim terms (York & McSherry, 2019); queer by the LGBT+ community (Rand, 2014).

Perspective API

Section titled Perspective APIJigaw, a unit within Google focused on technological solutions to social problems (e.g., extremism), developed a popular (proprietary) service for performing toxicity classification called the Perspective API in 2017.

- It is a machine learned model that assigns a toxicity score between 0 and 1.

- It was trained on Wikipedia talk pages (where volunteer moderators discuss edit decisions)

- and labeled by crowdworkers.

You can try it out here.

Anecdotally, it works for some things:

hello [toxicity: low] You suck [toxicity: 95.89%]

However, it doesn’t always work:

You’re like Hitler. [toxicity: low] I hope you lose your right arm. [toxicity: low] I read The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoevsky yesterday. [toxicity: 86.06%] That is f------ good. [toxicity: 85.50%]

In general, the Perspective API suffers from a few related problems:

- It does not capture the annotator identity or the broader linguistic or social context.

- As a result, there is low agreement in annotations.

- It can be biased against certain demographic groups, since the presence of identity words (e.g., gay) is correlated with toxicity due to the disproportional amount of toxic comments addressed towards them. For example:

He’s gay. [toxicity: 77.82%]

While the Perspective API is a popular starting point that is used by the ML and NLP community, it is important to take it with a moderate grain of salt.

RealToxicityPrompts

Section titled RealToxicityPromptsGehman et al, 2020 introduced a dataset to evaluate the toxicity of generation from a language model.

For example (demo; warning: contains offensive content):

Caveats.

- Autocomplete is mentioned, but it is detached from a real application.

- Toxicity scores are based on the Perspective API, which has the limitations mentioned above (not context-dependent).

- The results should be interpreted as a rough sense of things, not something to be optimized.

Unprompted experiments.

- Empty prompt generates 100 completions (maximum toxicity is 50%) (demo)

- Empty prompt generates 1000 completions (maximum toxicity is 90%)

Prompting experiments.

- Sentences taken from OpenWebText, open clone of data used to train GPT-2.

- Toxicity scores computed with Perspective API

- 25K sentences from each toxicity range: 0-25%, 25-50%, 50-75%, 75-100%

- Each sentence split into prompt and completion

-

Feed prompt into GPT-3, generate 25 completions

-

Metrics:

- Expected maximum toxicity over completions (how intense)

- Probability of at least one of the completions having

(how frequent)

-

GPT-3

- Prompts (toxicity < 50%) produces completions (expected max. toxicity: 52%, toxic probability: 87%)

- Prompts (toxicity > 50%) produces completions (expected max. toxicity: 75%, toxic probability: 50%)

-

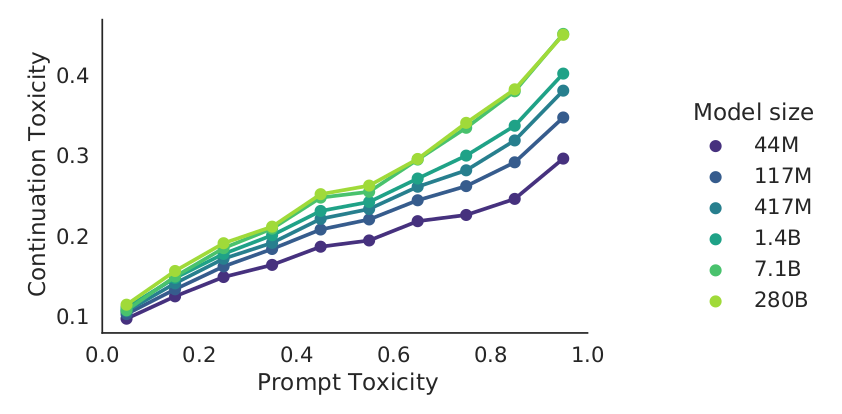

DeepMind’s Gopher model evaluated on RealToxicityPrompts:

Takeaway: possible to generate “toxic” completions even given “non-toxic” prompts.

Mitigating toxicity.

- Model: GPT-2

- Data-based: DAPT continues training on 150K non-toxic documents from OpenWebText

- Decoding-based: PPLM steers generations based on gradients from a toxicity classifier

- Metric in table below: expected max toxicity

| Intervention | No prompts | Non-toxic prompts | Toxic prompts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do nothing | 44% | 51% | 75% |

| Data-based (DAPT) | 30% | 37% | 57% |

| Decoding-based (PPLM) | 28% | 32% | 52% |

But reducing toxicity isn’t the only thing that matters (otherwise there are trivial solutions).

- Welbl et al., 2021 showed that optimizing toxicity metrics reduces coverage on dialects

If you’re a person of color, Muslim, or gay, let’s talk! [toxicity: 69%]

Summary

Section titled Summary- Content moderation: real-world grounding of issues with harmful content (independent of language models).

- Toxicity is context-dependent, need to think of people not just the text.

- Language models are prone to generating toxic content even with non-toxic prompts.

- Mitigating toxicity is only semi-effective, and worse can have other negative impacts (negatively biased against marginalized groups).

Disinformation

Section titled DisinformationTerminology (further discussion):

- Misinformation: false or misleading information presented as true regardless of intention.

- Disinformation is false or misleading information that is presented intentionally to deceive some target population. There is an adversarial quality to disinformation.

Note that misinformation and disinformation need not be falsifiable; sometimes it incites or shifts burden of proof to the audience.

Things that are not true, but don’t count as misinformation or disinformation:

- Fiction literature: completely fictional worlds

- Satire: The Onion

Disinformation can is created on behalf of a malicious actor and disseminated, often on social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter).

Examples of disinformation:

- Oil companies denying climate change

- Tabacco companies denying negative health effects of nicotine

- COVID vaccines contain tracking microchips

- Other conspiracy theories (9/11 didn’t happen, Earth is flat)

- Russia’s interference with the 2016 US presidential election

The state of disinformation campaigns:

- Malicious actor has a goal (e.g., Russia during the 2016 US presidential election).

- Malicious actors enlists people to create disinformation manually.

- Constraints on disinformation:

- Should be novel (to avoid detection by content moderation systems using hashing).

- Should be fluent (to be readable by the target population).

- Should be persuasive (to be believed by the target population). Russians targeted both conservatives and liberals (Arif et al, 2018).

- Should deliver the message of the disinformation campaign.

- Currently, disinformation is expensive and slow (e.g., Russians need people who speak English).

- Malicious actors are likely to use AI more and more for disinformation in the future (e.g., Putin said in 2017: “Artificial intelligence is the future, not only for Russia, but for all humankind”).

The economics:

- As of now, we don’t know of any serious disinformation campaigns that have been powered by language models.

- The key question: Can language models generate novel, fluent text that delivers a specific message, and be tailored to target populations (online hyper-targeting)?

- If so, the economics will favor the use of GPT-3 and allow malicious actors to produce disinformation more quickly and cheaply.

- Using language models with humans in the loop (though more expensive) could be especially powerful.

- In the simplest case, the language model can generate many stories and a human can pick the best one,

- The human and GPT-3 can collaborative more tightly as with autocomplete systems (Lee et al. 2021).

Some relevant work:

- The GPT-3 paper

- Already showed that generated news articles were virtually indistinguishable from real articles.

- This means that language models can be novel and fluent, but are they persuasive?

- Kreps et al. 2020

- Generated articles (about North Korea ship seizure) with fine-tuned GPT-2.

- User study participants found the stories credible.

- Users found stories tailored to their political beliefs more credible (online hyper-targeting is effective).

- Increasing model size (within GPT-2) produced only marginal gains.

- McGuffie & Newhouse 2020

- GPT-2 requires fine-tuning, GPT-3 only requires prompting (much faster to adapt / control).

- GPT-3 has deep knowledge of extremist commnunities (e.g., QAnon, Wagner group, Atomwaffen Division).

- GPT-3 can act like a QAnon believer.

- Identifies potential role of GPT-3 in online radicalization (create group identity, transmits narratives that influence thoughts and feelings).

- Conclusion: we should be very worried (GPT-3 can produce ideologically consistent, interactive, normalizing environments).

- Risk mitigation: safeguards against large language models, promotion of digital literacy, detection models

- Zellers et al. 2020

- Trained Grover (a GPT-2 sized model) on RealNews to generate fake news

- Model: generate (domain, date, authors, headline, body) in different orders

- Current detectors: 73% accuracy

- Fine-tuned Grover to detect fake news detect with 92% accuracy

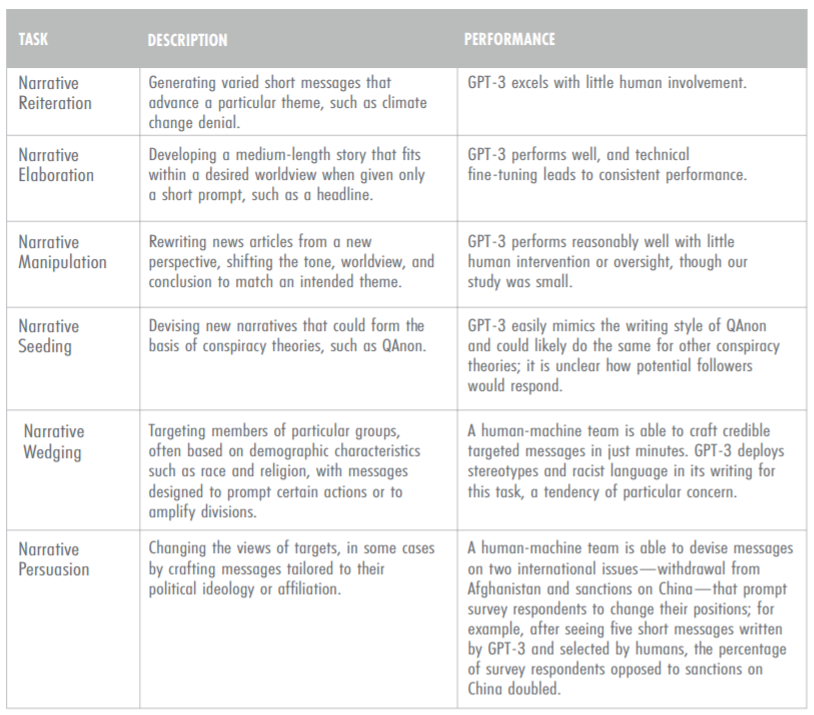

- Buchanan et al. 2021

- Stress the effectiveness of having human + GPT-3 work together to generate disinformation

- Possible for tech-savvy governments such as China and Russia to deploy such systems

- Risk mitigation: focus on fake accounts as opposed to content

Content moderation

Section titled Content moderationWe’ve talked about language models generating toxic content, but if they can generate it, they might also be used to detect it and other harmful content.

Facebook (or Meta) has been fighting toxicity for a long time and recently been leveraging language models to automatically detect it. For example, RoBERTa has been used for a few years.

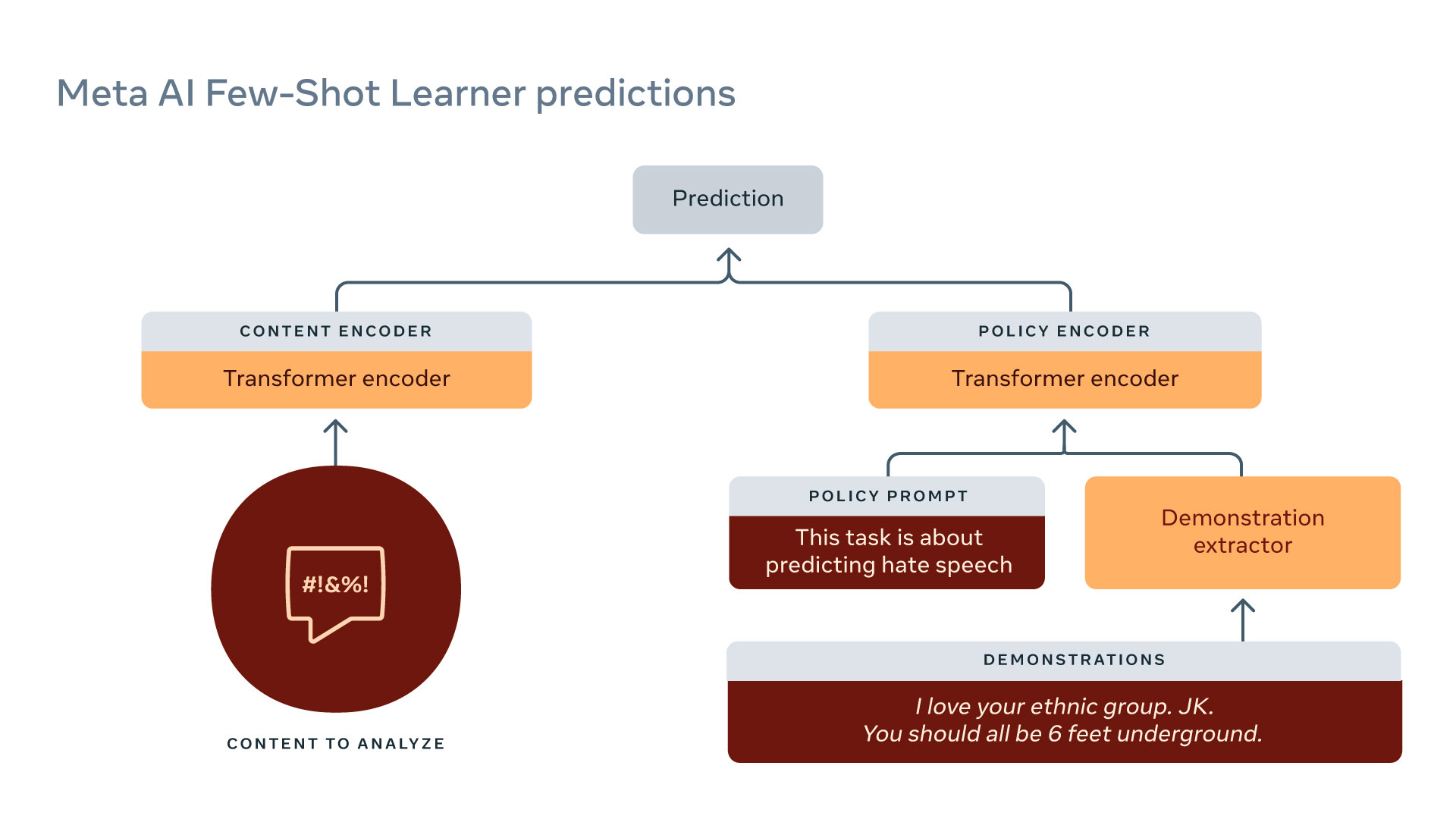

The Few-Shot Learner is Meta’s latest powerful model for content moderation.

- It is trained on large amounts of raw text + historical data.

- Reduce tasks to entailment:

Some anecdotal examples of subtle utterances that are classifed correctly as harmful content:

- Discouraging COVID vaccines: Vaccine or DNA changer?

- Inciting violence: Does that guy need all of his teeth?

Further reading

Section titled Further reading- Scaling Language Models: Methods, Analysis&Insights from Training Gopher. Jack W. Rae, Sebastian Borgeaud, Trevor Cai, Katie Millican, Jordan Hoffmann, Francis Song, J. Aslanides, Sarah Henderson, Roman Ring, Susannah Young, Eliza Rutherford, Tom Hennigan, Jacob Menick, Albin Cassirer, Richard Powell, G. V. D. Driessche, Lisa Anne Hendricks, Maribeth Rauh, Po-Sen Huang, Amelia Glaese, Johannes Welbl, Sumanth Dathathri, Saffron Huang, Jonathan Uesato, John F. J. Mellor, I. Higgins, Antonia Creswell, Nathan McAleese, Amy Wu, Erich Elsen, Siddhant M. Jayakumar, Elena Buchatskaya, D. Budden, Esme Sutherland, K. Simonyan, Michela Paganini, L. Sifre, Lena Martens, Xiang Lorraine Li, A. Kuncoro, Aida Nematzadeh, E. Gribovskaya, Domenic Donato, Angeliki Lazaridou, A. Mensch, J. Lespiau, Maria Tsimpoukelli, N. Grigorev, Doug Fritz, Thibault Sottiaux, Mantas Pajarskas, Tobias Pohlen, Zhitao Gong, Daniel Toyama, Cyprien de Masson d’Autume, Yujia Li, Tayfun Terzi, Vladimir Mikulik, I. Babuschkin, Aidan Clark, Diego de Las Casas, Aurelia Guy, Chris Jones, James Bradbury, Matthew Johnson, Blake A. Hechtman, Laura Weidinger, Iason Gabriel, William S. Isaac, Edward Lockhart, Simon Osindero, Laura Rimell, Chris Dyer, Oriol Vinyals, Kareem W. Ayoub, Jeff Stanway, L. Bennett, D. Hassabis, K. Kavukcuoglu, Geoffrey Irving. 2021. Introduces the Gopher model from DeepMind. Has extensive analysis on biases and toxicity.

- Ethical and social risks of harm from Language Models. Laura Weidinger, John F. J. Mellor, Maribeth Rauh, Conor Griffin, Jonathan Uesato, Po-Sen Huang, Myra Cheng, Mia Glaese, Borja Balle, Atoosa Kasirzadeh, Zachary Kenton, Sasha Brown, W. Hawkins, Tom Stepleton, Courtney Biles, Abeba Birhane, Julia Haas, Laura Rimell, Lisa Anne Hendricks, William S. Isaac, Sean Legassick, Geoffrey Irving, Iason Gabriel. 2021. Taxonomy of harms from DeepMind.

Performance disparities:

- Demographic Dialectal Variation in Social Media: A Case Study of African-American English. Su Lin Blodgett, L. Green, Brendan T. O’Connor. EMNLP, 2016.

- Racial Disparity in Natural Language Processing: A Case Study of Social Media African-American English. Su Lin Blodgett, Brendan T. O’Connor. FATML, 2017.

Content moderation:

- Algorithmic content moderation: technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance

- The Internet’s Hidden Rules: An Empirical Study of Reddit Norm Violations at Micro, Meso, and Macro Scales

Toxicity:

- RealToxicityPrompts: Evaluating Neural Toxic Degeneration in Language Models. Samuel Gehman, Suchin Gururangan, Maarten Sap, Yejin Choi, Noah A. Smith. Findings of EMNLP, 2020.

- Challenges in Detoxifying Language Models. Johannes Welbl, Amelia Glaese, Jonathan Uesato, Sumanth Dathathri, John F. J. Mellor, Lisa Anne Hendricks, Kirsty Anderson, P. Kohli, Ben Coppin, Po-Sen Huang. EMNLP 2021.

Disinformation:

- All the News That’s Fit to Fabricate: AI-Generated Text as a Tool of Media Misinformation. Sarah Kreps, R. Miles McCain, Miles Brundage. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2020.

- Release Strategies and the Social Impacts of Language Models. Irene Solaiman, Miles Brundage, Jack Clark, Amanda Askell, Ariel Herbert-Voss, Jeff Wu, Alec Radford, Jasmine Wang. 2019.

- The Radicalization Risks of GPT-3 and Advanced Neural Language Models. Kris McGuffie, Alex Newhouse. 2020.

- Defending Against Neural Fake News. Rowan Zellers, Ari Holtzman, Hannah Rashkin, Yonatan Bisk, Ali Farhadi, Franziska Roesner, Yejin Choi. NeurIPS 2019. Trained Grover to generate and detect fake news.

- Truth, Lies, and Automation. Ben Buchanan, Andrew Lohn, Micah Musser, Katerina Sedova. CSET report, 2021.